Some months back, I wrote a post about the basics of multilingual sites in SharePoint. The post was a good primer for anyone that needs to understand SharePoint-centric concepts regarding multilingual web sites. Unfortunately, the post didn’t really describe important details outside of the SharePoint sphere. In particular, the post excluded all the ASP.NET-centric details. In this post, I want to share at least some of those additional details.

Globalization

One of the early design goals that Microsoft had for SharePoint was that ASP.NET developers would be comfortable creating SharePoint-based solutions. The theory is that if you’re a competent ASP.NET developer, you can simply pick up the additional SharePoint API universe; SharePoint is a good .NET citizen, so this idea shouldn’t be a stretch.

Whether or not you believe a good ASP.NET developer could easily pick up SharePoint, SharePoint does borrow very heavily from many .NET facilities. With regard to multilingual sites, this includes the Globalization namespace.

The Globalization namespace is a group of classes that are responsible for allowing ASP.NET applications to understand the numerous languages and cultures that applications can target. It includes everything from calendar differences and languages to date/time formats and string comparisons (and a whole lot more). It also, importantly, provides a facility to allow developers to create a resource pool of commonly referred to assets (e.g. element labels, images). These assets are all referenced using standard labels, creating an index of asset variants for each culture. At runtime, based on the culture of the current user (usually indicated by a browser setting), the .NET framework will dynamically select the appropriate asset/resource based on a generic label describing that asset or resource.

Resources and Resource Files (RESX)

Resources or multilingual assets are defined in a Resource File (RESX). There’s a resource file for each culture represented in the application. All resource files use the same labels to describe the asset, but with a culture-specific value. For example, the text shown next to the text box where a user would enter their user ID to authenticate with the application would be an example of a reference resource.

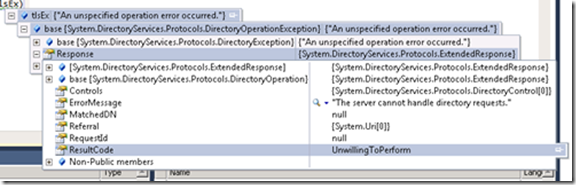

Figure 1 – Resource example for Login Page

In the RESX file, which is just XML, you’ll find the following entry

Figure 2 – Login_UserID label in the EN-US resource file

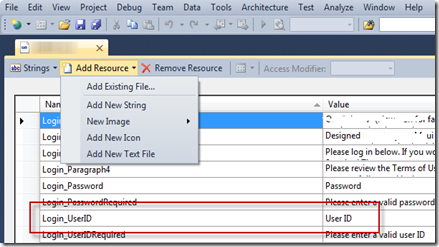

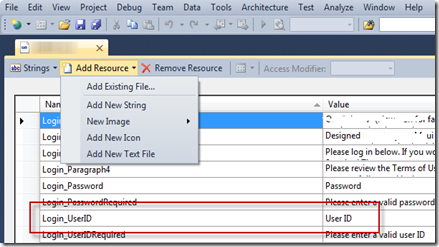

To add, edit or delete values, Visual Studio provides a “designer” view of the file. In the designer, you have the ability to quickly and easily define the various labels and the corresponding values. Figure 3 shows the Visual Studio interface for editing a RESX file.

Figure 3 – Visual Studio designer interface for RESX file

For every culture your application needs to support, you create a specific RESX file. Each file would be named for the culture it supports and every file would contain the same labels, with values corresponding to the specific culture. The example presented here, the RESX file is for the culture EN-US (US English). For more information on resource files, naming conventions and details on creating the files, take a look at this MSDN article on resource files.

In SharePoint terms, the RESX would correspond to a specific variation of the same culture. In effect, you will have at least one RESX file per variation. These files define elements of the user interface that end users do not supply. Whereas content on any given page is created and managed by content contributors, there are also elements, like the label for the User ID field on the login page, that are “baked” into the code of the application. RESX files provide a mechanism to define what that label will say in the context of a specific variation or culture selection (usually set by the browser displaying the page).

Information Architecture and Visual Design

Beyond the somewhat mechanical processes for inserting culture specific content into a page, a more critical aspect of multilingual sites is Information Architecture (IA). The IA defines the navigation paths (global navigation and its relationship to other sections and pages within the site) and the overall interface layout. This means the decisions about where various interface elements are placed, what nomenclature is used and what sort of content is shown are all made through and by the IA (both the person – Architect – and their output – Architecture).

When developing a multilingual web site, consider that the interface will be at least slightly and potentially radically different based on the language being displayed. The simplest example is word length. If we compare an interface in German and one in English, it’s very likely that there will be different space needs for labels in the navigation, as well as content. As a result, the IA must anticipate interface movement and allow for enough white space to accommodate an interface that will grow and shrink based on the language’s need. This too is a challenge for constructing HTML and JavaScript, since both components of the web page may need to “react” to language differences. However, beyond this relatively easy challenge, presenting content is matter of having the appropriate language-specific content.

A more complicated scenario is one involving differences in how a language is read. For Hebrew or Arabic (as two examples), the languages are read right to left. As a result, the whole orientation of the interface needs to shift. The main navigation will need to start from the right, global navigation elements will be positioned in the upper left and text will flow from right to left within the content sections. As such, you may require a unique master page and page layouts for these languages to sufficient accommodate the display differences. The same is true for languages that are read vertically instead of horizontally as in Manchu.

Continuing with the above example, you also have the challenge of fonts. Languages that utilize radically different character sets will require the IA and the designer to consider both font face and size choices. For example, for any font size choice in the cascading style sheet, will the text be readable across all languages represented by the site. Most European languages have characters with relatively little detail compared with Asian languages. Font sizes that are too small or font faces that carry too much embellishment may make detailed characters muddled or simply unreadable. As such, these choices represent both a visual design and information architecture challenge, since font size differences will also present spacing issues to resolve.

Bringing it all together

With all of the details provided in the two posts of this series, here’s a quick review of the important parts:

- When developing your Information Architecture for a multilingual site, include the various cultures included. Each culture, in SharePoint terms, will be a “variation.” A culture, remember, is a combination of a language and a country, represented like EN-UK (English – United Kingdom) or PT-PT (Portuguese – Portugal). This culture approach makes it easy to distinguish between two countries that share a broad language (e.g. Spanish), but differ in usage (e.g. Spain vs. Mexico).

- Developing an IA for a multilingual sites involves many more decisions and test cases to resolve than a single language site. It’s important to explore the implications for your specific IA based on the languages that need to be supported and, when the visual design is complete, any challenges a specific design might pose based on the supported languages.

- Within SharePoint, decide what variation will act as a the “primary” or source variation. This is the variation that will syndicate content to all other variations. For example, if the source variation is German (from Germany), your content will start in German; once a page is approved, it will be copied to the other language variations in your site collection (e.g. EN-UK, PT-PT). From there, each non-source variation will be responsible for translating, approving and publishing a language specific version of the German content.

- You will have at least one RESX file per variation. If you have lots of different cultures, you will have as many RESX files and they must all contain the same labels. Because labels are not evaluated during compile-time in Visual Studio, you’ll only discover missing (or conflicted) labels in a resource file at run time. This is not, obviously, a good user experience. As a result, you should thoroughly test and control the modification of RESX files. Take a look at this blog series from Carel Lotz regarding one approach to effective RESX management: http://fromthedevtrenches.blogspot.com/2011/04/managing-net-resx-duplication-part-1.html

- Think carefully about the taxonomy (aka organization) of variations and labels. As much as the IA process should define navigation, the overall taxonomy will drive label names and how labels are used in the application. For the project example in this post, we used labels tied to interfaces (interface name prepended on label name). This is one approach. However, this approach neglects opportunities to leverage labels across interfaces. Conversely, label use across interfaces can make maintenance more challenging as label changes will necessarily have different impacts across the application. Here, experimentation and testing are key.

- A SharePoint multilingual site is really a combination of SharePoint variations and .NET globalization. You must necessarily implement both; end users will leverage the variations component and your developers will have to provide matching RESX files for application-specific labels and static text.

As you may have surmised, there are a lot of details to consider when developing a multilingual web application. SharePoint does provide decent facilities to enable basic multilingual sites and the .NET framework provides loads of flexibility in implementation. Just be sure to consider the whole picture – it’s a combination of SharePoint centric constructs (aka variations), good information architecture/design and the technical “infrastructure” to make the whole solution work for end users.